Articles About Art - Images of Yam Gods

Art Information > Art Articles

> Images of Yam Gods

IMAGES OF YAM GODS: by Dr. Bridget Nwanze, University of

Port Harcourt, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

This paper describes the image of Ifejioku the yam god of Ossissa.The aim is to provide the

socio-religious background for understanding the divine origin and the sacred nature of yams in the

traditional belief of the Ossissa Igbo people. Ossissa is in the southern western part of Igbo

cultural area. The Igbo, most often referred to as Ibo, are a group of about six million people

located in southwestern Nigeria.The Igbo are the second largest group of the west African country,

Nigeria and have multiple dialects within the language. Interviews conducted with

some elders who are familiar with traditional custom of the village in February 2008 revealed that the

ordinarily simplified everyday way of life of the Ossissa Igbo man is centered around religion and

ancestors.The basic needs, it is believed can only be met if the ancestors give a nod of approval to

various requests.These requests range from right of life to the pleasure of the world. Hence for them

every visitor is greeted with an offer and breaking of kola nut which is preceded with pleasantries

and words of adoration for the forefathers and gods. Ossissa indigenes like many Igbo tribes celebrate

culture especially during the new yam festival which heralds the harvesting of yam crops.This

signifies the importance of the crop to their culture. It comes with dedication and paying of homage

to the gods for giving them a plentiful bounty. These ancestors are represented by images. The images

are symbolic and revered. The local tradition was that the images were made by women potters. They are

various and indigenous to their culture

IDENTITY

Religion is the controlling principle in Ibo existence. Although Christianity reached Ossissa as

early as 1896, traditional religious worship is still visible. The Ifejioku sculptural terracotta of

Ossissa is a symbolic image which represents the yam god – Ifejioku. This Ifejioku in sculptured

terracotta form convey very little of the impression they give in their actual place of use. Although

about eight different pieces have so far been discovered, extant whole pieces exist only in foreign

museums, especially in the Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh and the British Museum in London.

In Nigeria, very few of these terracottas exist. In Benin Museum, there exists partly broken

Ifejioku pieces while fragments of few of them have been found both in the National Museum in Lagos

and in the shrine of Ifejioku in Ossissa.

This paper is intended to relate three of the genre to its religious environment.

The existence of the divine Being and the invincible spirit world is natural to them.

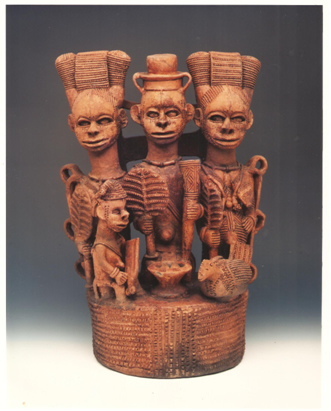

The three pieces of sculptural terracotta chosen here for description indicate that the number of

figures on the earthenware vary. They all consist of a major figure, invariably male, flanked on both

sides by subordinate females and males in varied small sizes. Like a collection of character in a

play, they wear a number of adornments peculiar to the area and carry a number of objects typical of

the area. While the priests were the custodians of these objects, the creations were by craftsmen and

artists who worked within the context of customs. Their imagination centered around and was informed

by the culture and scenes around them.

Three Ceramic altar pieces for the New Yam Harvest:

The Ossissa terracottas show themselves as a visual elegance with some functionality. They show

figures in their full bloom. The hairstyle must have been worn only by the wives of chiefs and also

made by only specialized hands. In the female figures, the potters have exemplified basic social roles

of women in the society – pregnant, nursing and serving as companions. The creation of women on

the ritual piece is contrary to the local idea that only males were allowed to worship at Ifejioku

shrine and that women do not own Ifejioku pots or shrine. Perhaps the reason for the centralization of

the male figure and the relationship between the various other forms on the Ifejioku sculptural pieces

is due to the people’s beliefs. Chief Izuegbu, one of the indigenes interviewed on the issue

opined that Ifejioku is an occupational deity because it serves the spiritual and material needs of

the people whose major occupation is farming. The people believed in the invisible world and the

remoteness of the supreme God, Chukwu, it was necessary to reach him through intermediaries.

These intermediaries are usually famous men who lived and died amongst them and are believed to live

in an invisible world. He further stated that farming was mainly a man’s occupation with

the support of his family members.

The oral tradition – according to another informant, Okwudike, which is historical in nature

claims that the beliefs of the people led them into the creation of art forms like the Ifejioku

terracotta, which ultimately served as intermediaries to Almighty God ‘Chukwu’. During the

new yam festival, prayers are said and blood sacrifice is sprinkled on the fragment of the images in

the shrine. Imagination led to variety of creativity, which at the end of the day suited the feelings

of the people. The artists served as intermediaries between the cult priests and their thoughts. They

needed more than imagination to be in contact with their fore – fathers. Okwudike stressed

that ‘farms belonged to men as heads of families’. Others also believed that imagination

of the worshipers may have spurred such creations as the Ifejioku terracotta.

MALE DOMINACE

On the reason for the sex of the central figure on the terracotta, the priests and elderly men

informed the researcher that their forefathers were great farmers and since it was the tradition of

the people to venerate ancestors, Ifejioku was conceived as farmers spirit who ensures productivity

and fertility. Although women and children also farmed, there was a choice of the male as a dominant

figure, a situation that mirrors male preference, and accepted superiority over women in public

domain. They believe that Ifejioku is a man who had wives whose duties were to produce children that

were needed to help in the farms. The presence of the central male figure as well as his Ikenga shows

the force that directs achievement. The values appreciated by members of the community regard

ancestors as mainly dead male parents. God is regarded as a man. The traditional ruler is a man.

Lineage is counted through the male line. Consequently, it should not look strange that the male

figure is projected. Female ancestors are not usually revered. The Ikenga, an altar of the hand

by which notables gain good fortune is purely owned and worshipped by men. Since those really treated

as deities are those who took title, married, had children and were successful farmers, it was obvious

why family members and other objects were included in the tableaux. In Oba Nwabueze’s opinion,

‘creating their ancestors without the family members could cause loneliness for the god’.

He needed companions to function and polygamy was also common practice in Ossissa. According to

another indigene, the terracotta reminds Ossissa indigenes of the role of man as well as family

members in farming. They are therefore believed to be portraits of respected chiefs or headsmen

who have died. On the question of whether the Ifejioku terracotta could be molded without the male

figure, one chief responded with the proverb “without the thumb, the hand cannot hold a

cutlass” underlining the indispensability of the man.

CONCLUSION

By associating these sculptures with ancestors, they have been highly charged with meanings.

They also seem to carry complex symbolic messages. Nevertheless their presence engages the

participation of living descendants and their ancestors. The artists may have believed that in order

to please the gods, there was need to present him with the favorable conditions he enjoyed while on

earth as well as create such offerings that may be acceptable by him. The belief by all is that the

identity and presence of these ancestors are inextricably bound to the terracotta. This presence

and power of past leaders or ancestors affirm the social expectation of the ruling chiefs to undergo

same process when they die. It should be evident at this point that through the synthesis of Ifejioku

art forms, there is an establishment of social and spiritual order through artistic creation.

Our oral literature being the source of the belief of the people cover a greater part in the realm of

Ossissa art. The human body is here used as a metaphor for the social body. The male

figure represents a chieftain with signs of status. Stories from everyday occurrences stressing

moral values and precedents leading to fame are used as basis to form logic to drive home

points. The artist on his part combines this logic with psychology through imagination to bring

about an accepted conclusion. The creators of Ifejioku pieces have also used symbolic aesthetic

qualities to create feelings of fear and commitment. Thus because written literature that could

remind worshippers of the past is missing, memory is aided by the use of symbols and images.

Such images like the Ifejioku is re-enacted in rituals and during the new yam festivals. The

artists have here created values expressing their individual feelings and preference as well as

communal values of the society. The Ifejioku terracotta is an embodiment of sociological and

cosmological messages.

NOTES

1. B. Nwanze, The IfeJIOKU Scuptural Terracotta of Ossissa, Dissertation,University of Ibadan,

Nigeria, 1999

2. C. Obuzor, Onotu Ukwu of Umu Osimili, oral interview, 10th August, 1997.

3. Charles Obuzor, Oral interviews 10th Augsut, 1997

4. B. Croizier, National Museums of Scotland, Letter 21st March 1997.

5. E. Okolugbo, A History of Christianity in Nigeria. The Ndiosimili and Ukwuani, Ibadan,

Daystar, Press, 1984.

6a M. Sadler, Arts of West Africa, London, Oxford University Press,

1935.

b. Equiano, Olaudah, The interacting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa

the African Norwich. 1794.

7. A. E. Afigbo, Towards a History of the Igbo speaking people of Nigeria, Ibadan,

Oxford University Press, 1975.

8. E. Isichei, Igbo worlds, an Anthology of Oral Histories and Historical Descriptions. London:

Macmillan Press, 1977.

9. K. O. Dike, Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta 1830- 1885, Lagos 1956.

10. M. A. Onwuejeogwu, An Igbo Civilization, Nri kingdom and Hegemony, Benin: Ethiopie

Publishing Corporation, 1981.

11. F. C. Ogbalu' Igbo Language and Culture, Ibadan, Oxford University Press, 1975

12. E. N. Emenanjo, Igbo Language and culture central Igbo, An Objective Appraisal,

Ibadan, Oxford University Press, 1975.

13. J. Adam; Comparative Study of Culture Trait

14. W. D. Baikie Voyage experience – Narrative of exploring; voyage 854, 1856.

15. A. G. Leonard, The Lower Niger and its Tribes. London, 1906.

16. N. W. Thomas, Anthropological report on the Ibo – speaking

peoples of Nigeria. Part I, London 1914.

17. P. A. Talbot, Tribes of the Niger Delta, London, Sheldon Press, 1926.

18. M.S.W. Jeffrey, The Umudri traditional origin,’ African Studies 15, 1956.

19. Agunwa, Jude C. U. The Agwu deity in Igbo religion. Fourth

Dimension Publishing Co., Ltd.. 1995.

20. T. Phillips (ed.), Africa, the art of a continent (London,

Royal)